Giant Pacific Octopus

Enteroctopus Dofleini

The Northeast Pacific is an ocean of record-holding species. Home to the fastest-growing organism, tallest sea anemone, speediest sea star, largest jellyfish, biggest sea turtle, and more.

Most well-known of all however, is no doubt the Giant Pacific octopus (GPO). The largest species of octopus on earth. While the size alone of these creatures can be mind-boggling, they are also infamous for their remarkable intelligence, playfulness, and curiosity.

In most cases, my artwork is inspired by a photo that I have taken of the associated creature in the wild, however in this instance I have cut corners and used a photo of the equally-charming Ruby octopus instead. I have included both this photo, and my favourite photo of a GPO below:

October 2016: A fully grown Giant pacific octopus graces us with a rare encounter. These animals only very rarely are seen out of their dens during the daytime. This octopus greeted us in astonishingly shallow water, no greater than 2m from the surface at high tide.

May 8th, 2020: A curious little Ruby octopus poses out in the open during a night dive in Campbell River, B.C. Just out of frame, a Green sea urchin towers above them, quite possibly offering haphazard shelter from predatory fishes.

📖 Description 📖

As the aforementioned largest species of octopus on earth, adult GPOs can often reach a weight of 50kg, and an arm-span of 6m. Several reports of GPOs reaching astounding sizes have been reported over the years, with the most impressive being of an individual that was 272kg, with arms reaching up to 9m across! An animal of such size is difficult to imagine. Unfortunately there are no photos available of this specimen, and for several reasons this report has been unfortunately considered ‘suspicious in nature’ [1].

Regardless, regular sized adult GPOs are still a force to be reckoned with. Octopuses are very muscular animals; just about everything below the eyes is made of muscle, and GPOs rarely back down from an opportunity to demonstrate their strength and intellect.

At the base of each arm is a bundle of nerve cells called a ganglion. These ganglia allow the arms to move and explore their surroundings with some independence from the Octopus’ brain [2]. In this sense, octopus arms each have a mind of their own, leading some to claim that octopuses have nine brains in total! If you have ever picked something up in one room and set it down in another without realizing it, you might have a pretty good idea of what it is like to be an octopus with uncooperative arms.

Each of these eight arms are lined with suckers which are used to grab prey and manipulate objects. Individual suckers are incredibly strong and when used together, It can be nearly impossible to escape their grasp.

July 2022: A fully grown GPO shows off its incredible eyes to my camera. Note the red speckles above and below the line-shaped pupil. These are chromatophores, and octopuses can change the colour of their eyes much like their skin.

🌎 Distribution 🌎

GPOs have a very wide distribution, encountered anywhere from Southern California, up through the entire Northeast Pacific coastline, and down as far as South Korea in the Western Pacific. Oddly enough, there are also reports of GPOs encountered in Hawaii, but there is little information to back up these observations [3].

Distribution of the Giant Pacific octopus, Enteroctopus dofleini. Suitable habitat depicted in red.

🏝 Habitat 🏝

GPOs can be encountered in virtually any coastal habitat, as they are known to travel great distances in search of prey. In British Columbia, they are regularly sighted on rocky reefs, eelgrass beds, kelp forests, and even the intertidal zone. Up to 90% of the time however, a GPO will be tucked away inside of a burrow or rocky crevice known as an octopus den. As they are vulnerable when out in the open, the den is very important for hiding away from predators.

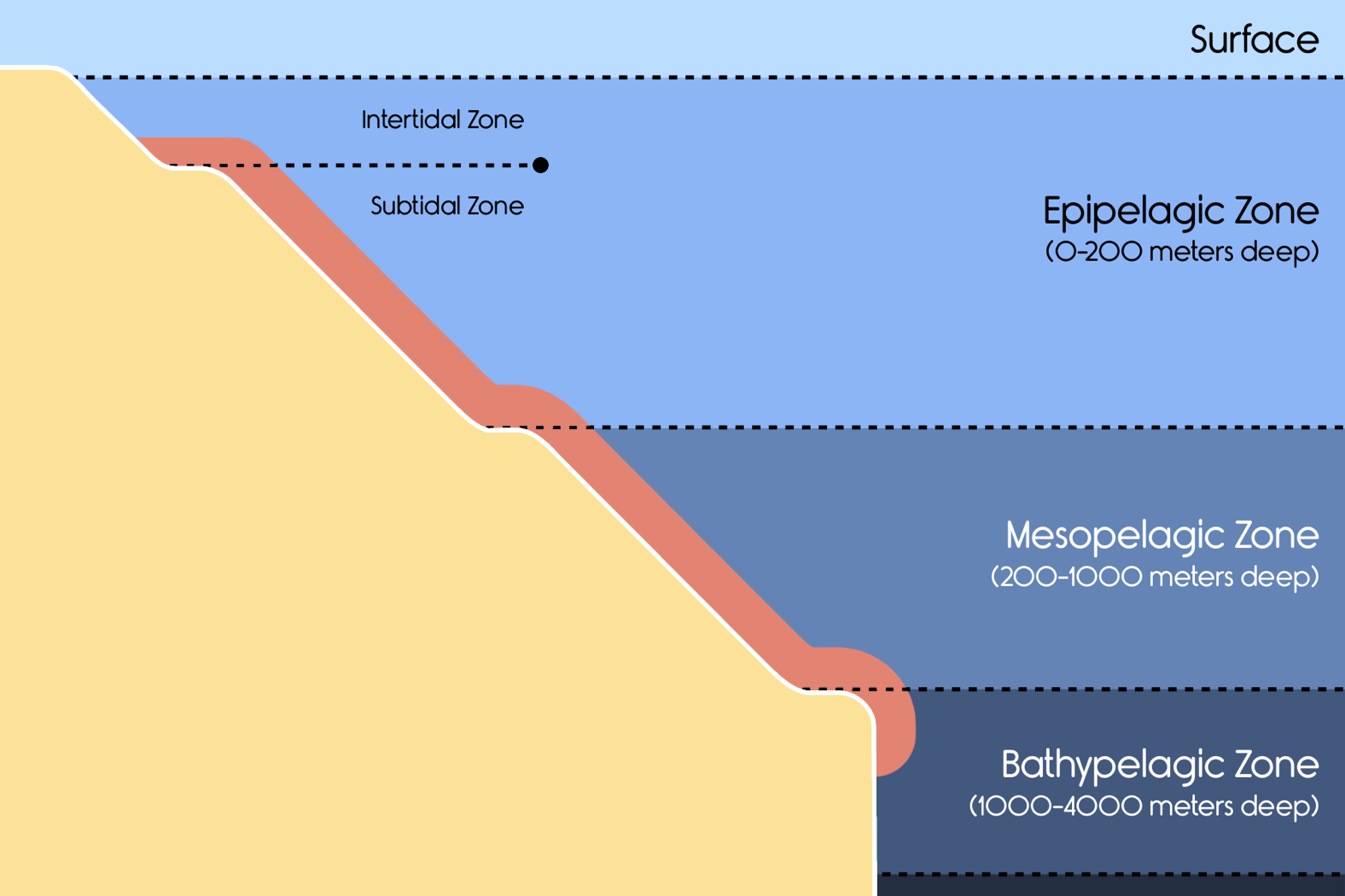

GPOs strongly prefer cold water to warm water, and this will influence where a GPO chooses to spend its time. In regions where temperatures rise considerably during the summer, GPOs have been reported to depart for deeper waters until shallow waters cool off in the fall. GPOs have been observed living as far deep as 1500m!

Depth of suitable habitat for the Giant Pacific octopus, Enteroctopus dofleini. Suitable habitat depicted in red. Not to scale.

🦐 Diet 🦐

Some may say GPOs like to play with their food, and some types of food are more fun to play with than others. In particular, GPOs prefer to feed on crabs such as the Red rock crab and Dungeness crab. They will hunt just about any creature with a shell however, including scallops, clams, and sea snails [4].

January 2020: A particularly photogenic Red rock crab seen in an eelgrass bed in Central Saanich, B.C. Potentially one of the GPO’s favourite snacks.

GPOs can eat up to 10% of their body weight at a time, and will grow incredibly fast when lots of food is available. In public aquariums and learning centres, aquarists have to be careful not to feed their octopuses too much, as they may rapidly outgrow their tank in a matter of months!

After a successful hunt, GPOs will haul their catches back to their den to feast in a safe environment. When the shells or bones of its prey have been picked clean, they toss them out of their den, giving scuba divers and researchers an opportunity to see what individual octopuses have been eating. The octopus in the photo below appears to have recently feasted on scallops, for instance:

December 2019: An adult GPO defensively retreats into its den. The remnants of its most recent meals are visible to the left. Scavenging Blood stars appear to be searching for scraps on the discarded scallop shells. Photographed off of Swordfish Island in Metchosen, B.C.

🐙 Life Cycle 🐙

GPOs, like all octopuses, live a relatively short life span. GPOs will live for anywhere between 3 to 5 years, which is actually quite a bit longer than most related species. GPOs are semelparous, meaning they only reproduce once in their lifetime, and die soon afterwards [4].

Female GPOs will lay up anywhere between 120,000 and 400,000 eggs. These eggs are laid in bundles called ‘festoons’ from the ceiling of the GPO’s den. These eggs can take up to 9 months to develop and hatch, and in this time their mother will refuse to leave the den or eat. The eggs need constant care and defence; eggs are very nutritious and are irresistible to sea snails and seastars.

September 2019: A festoon of eggs laid by the resident Ruby octopus at the Discovery Passage Aquarium. Eggs of the Giant Pacific Octopus are very similar in appearance.

An octopus begins its life as something called an octopus ‘paralarva’, which resembles a miniature adult. These paralarvae float amongst the plankton, hunting microscopic invertebrates until they grow large enough to fend for themselves on the sea floor.

December 2018: An octopus paralarva hunts among a plankton bloom. This creature was no larger than a pea and possibly less than one week old. Several other paralarva were seen, meaning that there could be a nearby octopus den that they have all hatched from. Photographed in Saanichton Bay in Central Saanich, B.C.

📚 References 📚

[1] High, W. L. (1976). The Giant Pacific Octopus. U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, Marine Fisheries Review, 38(9): 17–22.

[2] Horton, J. (2008, March 13). How Octopuses Work. How Stuff Works. https://animals.howstuffworks.com/marine-life/octopus1.htm

[3] World Register of Marine Species. (n.d.). Enteroctopus dofleini (Wûlker, 1910) Retrieved March 26, 2023, from https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=342305#sources

[4] Oceana. (n.d.). Giant Pacific Octopus. https://oceana.org/marine-life/giant-pacific-octopus/